For as long as I can remember my family had at least one pet and we’ve owned just about everything you can imagine: birds, ducks, geese, turkeys, fish, cats, dogs, goats, chickens (oh, the chickens) and the list goes on. I know what you’re thinking – what was it like on Old MacDonald’s Farm? – but we have never lived on a farm. All of those animals have been part of our family on less than a dozen acres of land and they were all pets. None of them were ever eaten…by humans.

I told you that so you would understand that having pets has always been a part of my life. There have been very few days when I’ve opened a door and an animal wasn’t waiting to be pet, or fed, or fed and then pet. We’re the kind of people who spend more money on healthcare for our pets than ourselves. My mom spends serious money saving the lives of baby chicks. I admire her kindness towards animals but question her financial planning abilities and mourn the loss of my inheritance. We take in strays, adopt, and if they are in pain when the time comes, put our pets to sleep.

So when I say that I question the humanity of having pets, it’s not stated lightly. It’s not some theoretical debate that I’m having with a group of philosophy students. It’s coming from a person who can fully understand both sides of the argument. However, when I stop and try to look at the problem objectively, it seems clear that pet ownership is nothing more than socially acceptable slavery.

Let’s be clear: I am in no way stating that the enslavement and subjugation of humans is equal to the owning of pets. Human slavery still exists, is inhuman, and must be abolished globally before we can even begin to consider ourselves “civilized”. It is interesting to note, however, that most of us do use the word “own” when describing our relationship with our pets. So we should ask ourselves: are pets slaves? If the answer is yes, why are we all OK with it?

Let’s look at the similarities between the enslavement of humans and what we do with our beloved pets. The first animal domesticated was the canine, many thousands of years ago. This occurred in a very logical way; wolves ate our trash and we thought they were cute so we fed them and they stuck around. Sounds harmless enough, but that’s not how things work today. Most pets are born into the homes they are expected to die in. Some are not allowed outdoors, where, as anyone with a pet knows, they desperately want to get to. Others aren’t allowed indoors because they are “too wild” or “too dirty”.

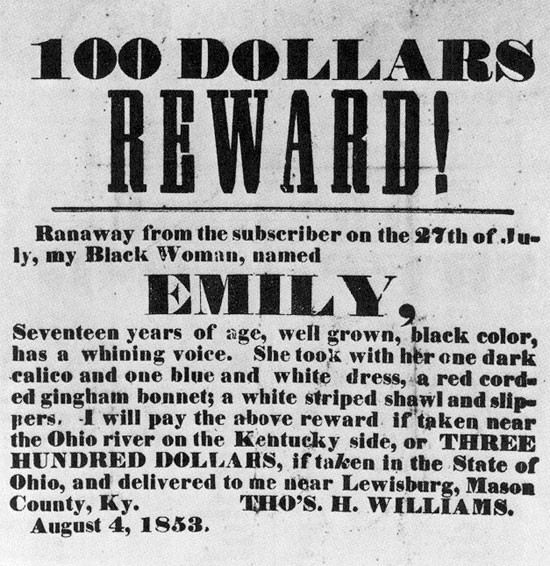

We have indoor and outdoor pets, just as there were house slaves and field slaves. House slaves were given better clothing, had a premium placed on cleanliness, were typically better educated, and provided with superior living conditions. They were not usually allowed to work any other jobs – to “go outside” – for fear that they would mix with the other slaves or otherwise sully their appearance. This is very similar to how we think about and treat our indoor pets. We even implant our animals with digital tracking devices so they can be returned to us should they get lost – escape – and be found. A more accurate flier would state that the pet has escaped and the owner wants it back and is willing to pay for their return, not unlike the advertisements taken out by slave owners when their property escaped.

When slaves were taken from their homes in Africa, they were considered to be “wild” in much the same way we consider “stray” animals to be wild, but look at the language we use. The word “stray” has a negative connotation, as if to say that the animal has left an acceptable group dynamic which, by the way, doesn’t exist. The only animals we consider acceptable are domesticated. This is eerily similar to the mentality of the whites who enslaved Africans considered to be heathens because they were uneducated in the ways of their subjugators and unfamiliar with the tenants of a particular religion.

Today we employ people who do nothing but gather up “loose” animals and eventually put them to death if no masters can be found. These people are often referred to as “collectors”, though the animals they collect are generally doing no harm. Although I’m not against some measure of population control for certain species whose natural predators we’ve eliminated, we’re going well beyond the pale when it comes to controlling certain types of animal populations. We routinely remove the reproductive organs of our pets, which we rather disturbingly refer to as “fixing” them, far more for our own convenience than theirs. Even the ASPCA doesn’t make a great case for this, and contradicts themselves by stating that “After sterilization, your cat may be calmer and less likely to exhibit certain behaviors, but his or her personality will not change.” I guess we can’t be expected to stop sterilizing animals any time soon when we’ve only recently stopped sterilizing humans in this country, but one can hope.

If you’ve ever taken in a stray animal, you know that they will try anything to escape, up to and including harming their captors. This behavior also occurred when slaves were captured and harsh punishments were doled out to discourage it. Our primary method of altering behavioral patterns with animals is a system of rewarding desired behavior. This is not much different than allowing a human to eat, or wash, or sleep, should they behave in an acceptable way. It’s certainly preferable to physical punishment, but the question that should be asked is why are we even concerned with domesticating wild animals? Why do we find their freedom so objectionable?

Part of the explanation seems to lie in the belief that they will live happier lives with us than if left alone. We’ll provide them with food, water, shelter and healthcare. They will be loved and fawned over. All of this may be true, but who are we to say that an animal would truly be happier in captivity, even if their prison is comparatively luxurious, than if they were free? How many thousands of stories have been written where a human, when given the choice between freedom and captivity, choose freedom even if the path was more difficult and the reward no more than the “right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint”?

Perhaps that’s why we train our pets. We don’t approve of their rebellious behavior, so we exert large amount of energy and money teaching them how we expect them to act, rewarding and punishing them accordingly. We rarely consider adapting to their needs, and instead lose our patience when an expectation isn’t met. In the end we’re hoping that they will do what we want and love us, alleviating any doubts we have about holding them against their will.

Alright, so we’re enslaving our pets. That much is clear, but what’s the alternative? If we release them, our beloved animals will surely perish in the wild which they are no longer prepared to inhabit, right? The very same argument was put forth by slaveholders when asked why they wouldn’t free their slaves. Many owners would not educate their slaves because the more education a slave received the more likely they were to demand their freedom or try to escape. Education was the open door to freedom that slave owners kept closed for generations. Pets are animals who, like humans, adapt to their environments. Although some may be ill-prepared and may die as a result, surely most would survive and carry on. That said, wide scale release is unlikely and even dangerous to animals and humans alike, for obvious reasons.

The more logical solution is to stop enslaving new pets; to end the cycle. Keep your existing pets, but don’t take on any new ones. The pets currently housed in shelters – prisons by another name – would all be adopted and reasonable population control measures could be put in place, eliminating the need for future shelters. In a few decades we’d have far fewer shelters and some veterinarians might need to find a new line of work, but we could theoretically end the enslavement of animals within a few decades.

But we all know that’s never going to happen. We love our pets and simply don’t want to lose that love. When one pet dies and an acceptable period of bereavement has been observed most of us will find a replacement. It’s the same process we use at the end of most of our relationships with humans.

Here is Pants sleeping. She longs for freedom but instead gets strokes and routinely pushed off of things.

I’m no different. I have a cat named Pants. She is adorable and my daily companion. I don’t want to free her even though I know I’m keeping her against her will. I see the way she looks beyond the door when it opens and I close it before she has a chance to escape, just as slaveholders withheld education for fear that one day their property would leave them. I feel guilty for owning my cat but I also tell myself that she’s better off, even though there is no way to be certain of that. In my circumstance I can’t give her the freedom of being an indoor/outdoor cat because I live on the top floor of an apartment building, but even if I could I wouldn’t. I don’t want to be inconvenienced by more dirt or fleas or visits to the vet to keep her the way I want her. Just as Washington and Jefferson wouldn’t free their slaves for fear of poverty befalling them, I won’t free Pants for fear of being alone.